In an earlier post, “Subjective probability and a puzzle about theory confirmation” I proposed that we distinguish between confirmation and evidential support. But the words “evidence” and “confirmation” have been so closely linked in the literature, and probably in common use as well, that it may be hard to make such a distinction.

Here I will use an example (more or less historical) to show how it can be natural to distinguish evidential support from confirmation, and why evidential support is so important apart from confirmation. (At the end I’ll take up how that relates to the puzzle set in the earlier blog.)

Cartesian physics did not die with Descartes, and Newton’s theory too had to struggle for survival, for almost a century. In an article in 1961 Thomas Kuhn described the scientific controversy in the 18th century, focused on the problem

“of deriving testable numerical predictions from Newton’s three Laws of motion and from his principle of universal gravitation […]The first direct and unequivocal demonstrations of the Second Law awaited the development of the Atwood machine, … not invented until almost a century after the appearance of the Principia”.

Descartes had admitted only quantities of extension (spatial and temporal) in physics, these being the only directly measurable ones. Newton had introduced the theoretical quantities of mass and force, and the Cartesian complaint was that this brought in unmeasurable ‘occult’ quantities.

The Newtonians’ reply was: No, mass and force are measurable! The Atwood machine was a putative measurement apparatus for the quantity mass.

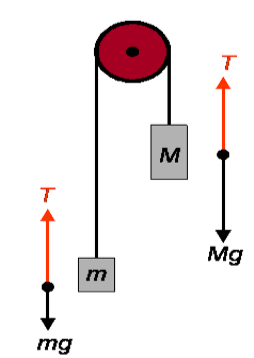

This ‘machine’ described by the Reverend George Atwood in 1784 is still sometimes used in classroom demonstration experiments for Newtonian mechanics. Atwood describes the machine, pictured below, as follows:

“The Machine consists of two boxes, which can be filled with matter, connected by an string over a pulley. … Result: In the case of certain matter placed in the boxes, the machine is in neutral equilibrium regardless of the position of the boxes; in all other cases, both boxes experience uniform acceleration, with the same magnitude but opposite in direction.”

Newton’s second law implies that the acceleration equals g[(M-m)/(M+m)]. Assuming the second law, therefore, it is possible to calculate values for the theoretical quantities from the empirical results about the recorded acceleration. The value of g is determined via the acceleration of a freely falling body (also assuming the second law), hence after measuring the acceleration a short calculation then determines the mass ratio M/m.

How does this strike a Cartesian? Their obvious reply must surely be that Atwood didn’t at all show that Newtonian mass is a measurable quantity! He was begging the question, for he was assuming principles from Newton’s theory.

Not only did Atwood not do anything to show that Newtonian mass is a measurable quantity, except relative to Newtonian physics (= on the assumption that the system is a Newtonian system) — he did not do anything to confirm Newton’s theory, in Cartesian eyes. From their point of view, or from any impartial point of view, this was a petitio principii.

But Cartesians had no right to sneer. For Atwood opened the road to the confirmation of many empirical results, brought to light by Newton’s approach to physics.

First of all it was possible to confirm concordance in all the results from using Atwood’s machine, and secondly their concordance with results of other empirical set-ups that counted as measurements of mass for Newtonian physics. In addition, as Mach pointed out later in his discussion of Atwood’s machine, it made it possible to measure with greater precision the constant acceleration postulated in Galileo’s law of falling bodies, a purely empirical quantity.

It was Atwood’s achievement here to show that the theory was, with respect to mass at least, empirically grounded: mass is measurable under certain conditions relative to (or: supposing) Newton’s theory, and there is concordance in the results of such measurements. When that is so, for quantities involved in the theory, and only when that is so, is the theory applicable in practical, empirically specifiable situations, for prediction and manipulation.

This is what I want to give as paradigm example of evidential support. Newton’s theory was rich enough to allow for the design of Atwood’s machine, with results that are significant and meaningful relative to that theory. Certainly there was a lot of confirmation, namely of empirical regularities and correlations, brought to light and put to good practical use, thereby demonstrating that Newton’s theory was a good, well-working theory in physics. Whether the description of nature in terms of Newton’s theoretical quantities was thereby confirmed in Cartesian or anyone else’s eyes, ceased to matter.

In the earlier blog I showed how a theory’s initial postulate could remain un-confirmed while the theory as a whole is being confirmed, in tests of its empirical consequences. If we just think about the updating of our subjective probabilities then that initial postulate would never become more likely to be true (and of course the entire theory cannot get to be more likely to be true than that initial part!).

But the evidential support for the theory, which is gained by a combination of empirical results and calculations based on the theory itself (in the style of Glymour’s ‘bootstrapping’) extends to all parts of the theory, including the initial postulates. So evidential support, which comes from experiments whose design is guided the theory itself, and whose results are understood in terms of that very theo outstrips confirmation, and should be distinguished from confirmation.