In his early papers Clark Glymour mounted a devastating attach on the hypothetico-deductive method and associated ideas about confirmation. Instead he offered his account of relevant evidence, and developed it into what he called his bootstrapping method.

Baron von Münchhausen pulled himself up by his bootstraps — a theory obtains evidential support from evidence via calculations within the theory itself, drawing on parts of that very theory. This understanding of the role of evidence in scientific practice was a further development of Duhem’s insight about the role of auxiliary hypotheses and of Weyl’s insistence that measurement results are obtained via theoretical calculations, based on principles from the very theory that is at issue.

Glymour’s account involves only deductive implication relations. But within these limits it arrives at the conclusion as I listed in the previous blog on a puzzle about theory confirmation. For an important result concerning the logic of relevant evidence developed in Glymour’s book is this:

If T implies T’ and E is consistent with T, and E provides[weakly, strongly] relevant evidence for consequence A of T’ relative to T, then E also provides this for A relative to T.

Here T’ may simply be the initial postulates that introduced the theory. In some of the examples, T’ may have no relevant evidence at all, or may even not be testable in and by itself. A whole theory may be better tested than a given subtheory. In some of the examples T’ may have no relevant evidence at all, or may even not be testable in and by itself.

This should have been widely noted. It upends entirely the popular, traditional impression that ‘the greater the evidential support the higher the probability’! For the probability of the larger theory T cannot be higher than that of its part T’, while T can at the same time have much larger evidential support.

In 2006 Igor Douven and Wouter Muijs published a paper in Synthese that introduces probability relations into Glymour’s account (“Bootstrap Confirmation Made Quantitative”). In view of the above, and of the puzzle for confirmation in my previous blog, it made sense to ask whether a similar result could be proved for this version.

Recall, the puzzle was this.

A theory may start with a flamboyant first postulate, which is typically, if just taken by itself, not even testable. Let’s call it A. Then new postulates are added as the theory is developed, and taken altogether they make it possible to design an experiment to test the theory, with positive empirical result, call it E.

Now, at the outset, the prior probability would naturally have A and E mutually irrelevant, since any connection between them would emerge only from the combination of A with other postulates introduced later on. So for prior probability P, P(A|E) = P(A) = P(A)

What we found that was that in this case, even when the probability of the entire theory increases when evidence E is assimilated, the probability of A does not change. And similarly when the evidence is information held with less than certainty, so that Jeffrey conditionalization is applied.

So how does this result fare on Douven and Meijs’ account? Here is their definition:

(Probabilistic Bootstrap Confirmation) Evidence E probabilistically bootstrap confirms theory T = {H1, . . . , Hn} precisely if p(T & E) > 0 and for each Hi in T it holds that

1. there is a part T’ of T such that Hi is not in T’ and p(Hi | T’ & E) > p(Hi | T’); and

2. there is no part T” of T such that p(Hi | T” & E) < p(Hi | T ”).

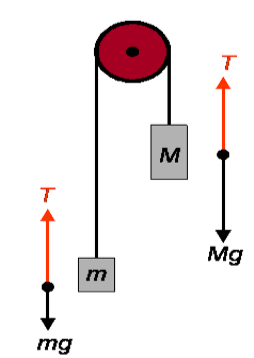

The following diagram now shows what happens on this account when the initial postulate and the eventual evidence are mutually probabilistically independent.

So we see here again that in this case, the propability of the initial postulate is not changed. And although the probability of the theory as a whole does increase, it just goes from small to less small, for it can never exceed the probability of its initial postulate.

Igor Douven and I had a very interesting correspondence about this. Douven immediately produced and example in which the probability of the initial postulate decreased. In that example, of course, the prior probability relationship between the initial postulate and the eventual evidence is not one of mutual independence. But in this way too, it is clear that in epistemology it is not the case that ‘a rising tide lifts all boats’.